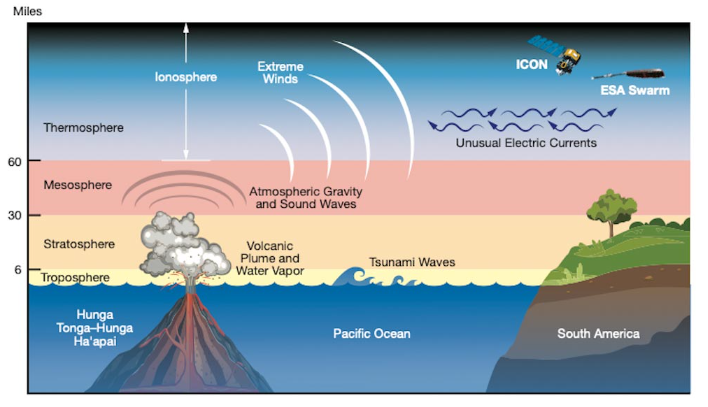

When a South Pacific volcano called Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai exploded on the afternoon of 15 January 2022, most of the world was taken by surprise. Few, in fact, had even heard of the mountain because it is mostly underwater, in the Kingdom of Tonga.

But the eruption was more than a curiosity. It produced a giant thump heard at least as far away as Fiji, 700 kilometres north-west. The same thump was later picked up worldwide by instruments designed to monitor for nuclear tests.

“This is the largest infrasound (ultra-low frequency) event we’ve ever seen,” R. J. Le Bras of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organisation said last month at a meeting of the Seismological Society of America (SSA) in Seattle, US.

But how big exactly was it?

Vulcanologists rate eruptions on an eight-point explosivity index (VEI), in which each one-point increase represents a 10-fold increase in power. The eruption of America’s Mt St Helens in 1980 was VEI-5. The 1991 eruption of Mt Pinatubo in The Philippines was VEI-6. Ditto for the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa in Indonesia. The biggest in recorded history, the 1815 eruption of Mt Tambora, also in Indonesia, was VEI-7.

As for Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai? Scientists are still struggling to be sure, but it looks to have been somewhere in the VEI-6 range, and probably the biggest since Tambora.

Part of the difficulty in determining its exact magnitude comes from its remoteness. But a bigger complication is the fact it occurred underwater.

Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is the crest of a giant submarine volcano which in 2014–15 briefly drew attention when a much milder eruption caused it to break the surface and create what was then the world’s newest island.

The 2022 eruption, however, was entirely beneath the waves. That creates a problem, because one of the ways to determine the VEI is by measuring the amount of lava accompanying the explosion. In this case, while much of that lava was blown out of the water and into a giant plume of volcanic ash, much also presumably remained underwater. That makes it hard to determine exactly how much there was, in total.

Luckily, measuring the amount of lava isn’t the only way to estimate an eruption’s power. It can also be done by looking at the height and size of the ash plume, and on that metric, Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai was off the chart. Instruments on NASA satellites estimated it to have to reached as high as 58km.

Read more at: Cosmomag